I have a love/hate relationship with calculus: it demonstrates the beauty of math and the agony of math education.

Calculus relates topics in an elegant, brain-bending manner. My closest analogy is Darwin’s Theory of Evolution: once understood, you start seeing Nature in terms of survival. You understand why drugs lead to resistant germs (survival of the fittest). You know why sugar and fat taste sweet (encourage consumption of high-calorie foods in times of scarcity). It all fits together.

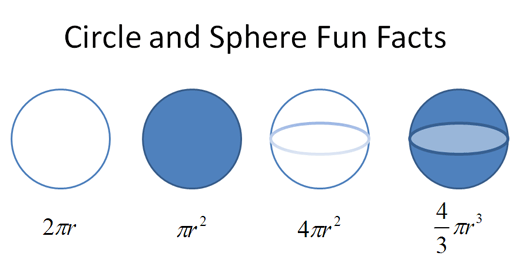

Calculus is similarly enlightening. Don’t these formulas seem related in some way?

They are. But most of us learn these formulas independently. Calculus lets us start with “circumference = 2 * pi * r” and figure out the others — the Greeks would have appreciated this.

Unfortunately, calculus can epitomize what’s wrong with math education. Most lessons feature contrived examples, arcane proofs, and memorization that body slam our intuition & enthusiasm.

It really shouldn’t be this way.

Math, art, and ideas

I’ve learned something from school: Math isn’t the hard part of math; motivation is.Specifically, staying encouraged despite

- Teachers focused more on publishing/perishing than teaching

- Self-fulfilling prophecies that math is difficult, boring, unpopular or “not your subject”

- Textbooks and curriculums more concerned with profits and test results than insight

“…if I had to design a mechanism for the express purpose of destroying a child’s natural curiosity and love of pattern-making, I couldn’t possibly do as good a job as is currently being done — I simply wouldn’t have the imagination to come up with the kind of senseless, soul-crushing ideas that constitute contemporary mathematics education.”

Imagine teaching art like this: Kids, no fingerpainting in kindergarten. Instead, let’s study paint chemistry, the physics of light, and the anatomy of the eye. After 12 years of this, if the kids (now teenagers) don’t hate art already, they may begin to start coloring on their own. After all, they have the “rigorous, testable” fundamentals to start appreciating art. Right?

Poetry is similar. Imagine studying this quote (formula):

“This above all else: to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as night follows day, thou canst not then be false to any man.”

–William Shakespeare, Hamlet

It’s an elegant way of saying “be yourself” (and if that means writing irreverently about math, so be it). But if this were math class, we’d be counting the syllables, analyzing the iambic pentameter, and mapping out the subject, verb and object.

Math and poetry are fingers pointing at the moon. Don’t confuse the finger for the moon. Formulas are a means to an end, a way to express a mathematical truth.

We’ve forgotten that math is about ideas, not robotically manipulating the formulas that express them.

Ok bub, what’s your great idea?

Feisty, are we? Well, here’s what I won’t do: recreate the existing textbooks. If you need answers

right away for that big test, there’s plenty of

websites,

class videos and

20-minute sprints to help you out.

Instead, let’s share the core insights of calculus. Equations aren’t enough — I want the “aha!” moments that make everything click.

Formal mathematical language is one just one way to communicate. Diagrams, animations, and just plain talkin’ can often provide more insight than a page full of proofs.

But calculus is hard!

I think anyone can appreciate the core ideas of calculus. We don’t need to be writers to enjoy Shakespeare.

It’s within your reach if you know algebra and have a general interest in math. Not long ago, reading and writing were the work of trained scribes. Yet today that can be handled by a 10-year old. Why?

Because we expect it. Expectations play a huge part in what’s possible. So expect that calculus is just another subject. Some people get into the nitty-gritty (the writers/mathematicians). But the rest of us can still admire what’s happening, and expand our brain along the way.

It’s about how far you want to go. I’d love for everyone to understand the core concepts of calculus and say “whoa”.

So what’s calculus about?

Some

define calculus as “the branch of mathematics that deals with limits and the differentiation and integration of functions of one or more variables”. It’s correct, but not helpful for beginners.

Here’s my take: Calculus does to algebra what algebra did to arithmetic.

- Arithmetic is about manipulating numbers (addition, multiplication, etc.).

- Algebra finds patterns between numbers: a2 + b2 = c2 is a famous relationship, describing the sides of a right triangle. Algebra finds entire sets of numbers — if you know a and b, you can find c.

- Calculus finds patterns between equations: you can see how one equation (circumference = 2 * pi * r) relates to a similar one (area = pi * r2 ).

Using calculus, we can ask all sorts of questions:

- How does an equation grow and shrink? Accumulate over time?

- When does it reach its highest/lowest point?

- How do we use variables that are constantly changing? (Heat, motion, populations, …).

- And much, much more!

Algebra & calculus are a problem-solving duo: calculus finds new equations, and algebra solves them. Like evolution, calculus expands your understanding of how Nature works.

An Example, Please

Let’s walk the walk. Suppose we know the equation for circumference (2*pi*r) and want to find area. What to do?

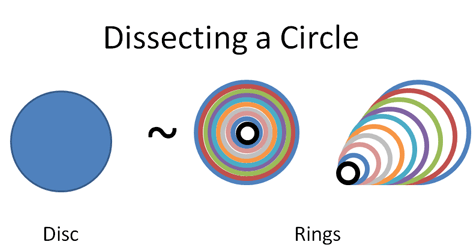

Realize that a filled-in disc is like a set of Russian dolls.

Here are two ways to draw a disc:

- Make a circle and fill it in

- Draw a bunch of rings with a thick marker

The amount of “space” (area) should be the same in each case, right? And how much space does a ring use?

Well, the very largest ring has radius “r” and a circumference 2 * pi * r. As the rings get smaller their circumference shrinks, but it keeps the pattern of 2 * pi * current radius. The final ring is more like a pinpoint, with no circumference at all.

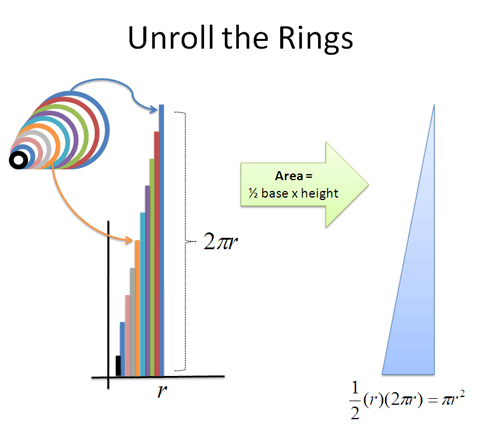

Now here’s where things get funky. Let’s unroll those rings and line them up. What happens?

- We get a bunch of lines, making a jagged triangle. But if we take thinner rings, that triangle becomes less jagged (more on this in future articles).

- One side has the smallest ring (0) and the other side has the largest ring (2 * pi * r)

- We have rings going from radius 0 to up to “r”. For each possible radius (0 to r), we just place the unrolled ring at that location.

- The total area of the “ring triangle” = 1/2 base * height = 1/2 * r * (2 * pi * r) = pi * r2, which is the formula for area!

Yowza! The combined area of the rings = the area of the triangle = area of circle!

This was a quick example, but did you catch the key idea? We took a disc, split it up, and put the segments together in a different way. Calculus showed us that a disc and ring are intimately related: a disc is really just a bunch of rings.

This is a recurring theme in calculus: Big things are made from little things. And sometimes the little things are easier to work with.

A note on examples

Many calculus examples are based on physics. That’s great, but it can be hard to relate: honestly, how often do you know the equation for velocity for an object? Less than once a week, if that.

I prefer starting with physical, visual examples because it’s how our minds work. That ring/circle thing we made? You could build it out of several pipe cleaners, separate them, and straighten them into a crude triangle to see if the math really works. That’s just not happening with your velocity equation.

A note on rigor (for the math geeks)

I can feel the math pedants firing up their keyboards. Just a few words on “rigor”.

Did you know we don’t learn calculus the way Newton and Leibniz discovered it? They used intuitive ideas of “fluxions” and “infinitesimals” which were replaced with limits because“Sure, it works in practice. But does it work in theory?”.

We’ve created complex mechanical constructs to “rigorously” prove calculus, but have lost our intuition in the process.

We’re looking at the sweetness of sugar from the level of brain-chemistry, instead of recognizing it as Nature’s way of saying “This has lots of energy. Eat it.”

I don’t want to (and can’t) teach an analysis course or train researchers. Would it be so bad if everyone understood calculus to the “non-rigorous” level that Newton did? That it changed how they saw the world, as it did for him?

A premature focus on rigor dissuades students and makes math hard to learn. Case in point: e is technically defined by a limit, but the

intuition of growth is how it was discovered. The natural log can be seen as an integral, or the

time needed to grow. Which explanations help beginners more?

Let’s fingerpaint a bit, and get into the chemistry along the way.

Where next?

My goal is to begin presenting a beautiful, oft-maligned subject in a new light. Many ideas are more intuitive than you think:

My knowledge of calculus is still very mechanical, but I know this can change. As I explore this topic I’ll cover the insights that worked, hoping you’ll chime in with what has helped you. Here’s the first:

Happy math

then

then  where n is a positive integer. The derivative reflects the instantaneous rate of change of the function at any value x. The derivative is also a function of x whose value is dependenton x.

where n is a positive integer. The derivative reflects the instantaneous rate of change of the function at any value x. The derivative is also a function of x whose value is dependenton x. then

then  where n is a positive integer. The derivative reflects the instantaneous rate of change of the function at any value x. The derivative is also a function of x whose value is dependenton x.

where n is a positive integer. The derivative reflects the instantaneous rate of change of the function at any value x. The derivative is also a function of x whose value is dependenton x. By definition the derivative of a dependent variable, f, is

By definition the derivative of a dependent variable, f, is  , which is the instantaneous rate of change of f with respect to x at any condition x. The right side of the function,

, which is the instantaneous rate of change of f with respect to x at any condition x. The right side of the function,  , represents the independent variable whose derivative is

, represents the independent variable whose derivative is

By definition the derivative of a dependent variable, f, is

By definition the derivative of a dependent variable, f, is  , which is the instantaneous rate of change of f with respect to x at any condition x. The right side of the function,

, which is the instantaneous rate of change of f with respect to x at any condition x. The right side of the function,  , represents the independent variable whose derivative is

, represents the independent variable whose derivative is

, the derivative of the dependent variable is,

, the derivative of the dependent variable is,  , and the derivative of the independent variable is

, and the derivative of the independent variable is  . Thus differentiating a function results in a new function of x, where

. Thus differentiating a function results in a new function of x, where  . The derivative is called

. The derivative is called  , read “f prime of x”, and it represents the derivative of a function of x with respect to the independent variable, x.. If

, read “f prime of x”, and it represents the derivative of a function of x with respect to the independent variable, x.. If  , then:

, then: , the derivative of the dependent variable is,

, the derivative of the dependent variable is,  , and the derivative of the independent variable is

, and the derivative of the independent variable is  . Thus differentiating a function results in a new function of x, where

. Thus differentiating a function results in a new function of x, where  . The derivative is called

. The derivative is called  , read “f prime of x”, and it represents the derivative of a function of x with respect to the independent variable, x.. If

, read “f prime of x”, and it represents the derivative of a function of x with respect to the independent variable, x.. If  , then:

, then:

gives the instantaneous rate of change of f(x) as a function of any value, x. Remember that the rate of change of a function other than a line is not constant. Its value changes as x changes.

gives the instantaneous rate of change of f(x) as a function of any value, x. Remember that the rate of change of a function other than a line is not constant. Its value changes as x changes.

, changes between two points

, changes between two points  , we simply enter in the two values for the independent variable x and then calculate the difference between the dependent variable, f, for those given conditions. Remember that a variable is nothing more than a dimension that is allowed to change or take on any value. Thus, from

, we simply enter in the two values for the independent variable x and then calculate the difference between the dependent variable, f, for those given conditions. Remember that a variable is nothing more than a dimension that is allowed to change or take on any value. Thus, from , the change in the independent variable , referred to as

, the change in the independent variable , referred to as  is:

is:

is:

is:

refers to an interval over which we are analyzing the change in the dependent dimension, f.. The second point

refers to an interval over which we are analyzing the change in the dependent dimension, f.. The second point  can be written in terms of the first point

can be written in terms of the first point  plus the change in the variable,

plus the change in the variable,

to

to  is

is  , which can also be written as:

, which can also be written as:

from x=3 to x=5 , where

from x=3 to x=5 , where  is 5 - 3 = 2 is:

is 5 - 3 = 2 is:

d=distance

d=distance , reduce the three dimensional function to one of two-dimensions for time as a function of distance, d.

, reduce the three dimensional function to one of two-dimensions for time as a function of distance, d. , from d = 0 to d = 100m

, from d = 0 to d = 100m , over each interval.

, over each interval.